Ever wondered why some programs launch instantly, executing commands with lightning speed, while others feel a little sluggish, taking a moment to "think" before they act? The secret often lies deep within how their code is transformed from human-readable instructions into something a computer's processor can understand and execute. This fascinating journey, powered by Code Compilation & Interpretation, is fundamental to program execution speed and efficiency.

At its heart, the difference between compilation and interpretation is about when and how your code gets translated into machine language—the raw binary instructions that your computer’s CPU can directly process. Understanding this distinction isn't just academic; it empowers you to make informed decisions that drastically impact your application's performance, development cycle, and portability.

At a Glance: What You'll Learn

- Compiled vs. Interpreted: The core difference and why it matters for speed.

- The Compilation Workflow: How source code becomes finely tuned machine code.

- Interpreter Mechanics: The dynamic, line-by-line translation process.

- The Rise of JIT: How Just-in-Time compilation blurs the lines and turbocharges performance.

- Performance Deep Dive: Why compiled languages traditionally offer superior speed.

- Beyond Speed: The significant advantages of interpreted languages for development and flexibility.

- Making the Right Choice: Practical guidance for selecting the best approach for your project.

The Fundamental Divide: Compiled vs. Interpreted

Imagine you've written a novel in English, and you want someone who only speaks Mandarin to read it. You have two primary options:

- Translate the entire book upfront: You hire a translator to convert the whole novel into Mandarin, print a new edition, and then give them the complete Mandarin book. This is akin to compilation.

- Translate chapter by chapter (or even sentence by sentence) as they read: You sit with the reader and translate each part of the book aloud as they go along. This is like interpretation.

In the world of programming, the "novel" is your source code (e.g., Python, C++, JavaScript), and the "Mandarin-only reader" is your computer's processor, which only understands its specific machine code.

Compiled Languages: The Pre-Translated Powerhouses

With a compiled language, your source code goes through a dedicated program called a compiler. This compiler translates your entire program into machine code before it ever runs. The output is a standalone executable file (like a .exe on Windows or an .app on macOS) that your computer can run directly.

- Key Characteristic: The translation happens once, producing a binary file optimized for a specific hardware architecture and operating system.

- Examples: C, C++, Go, Erlang, Haskell, Rust. These languages are often chosen for systems programming, game development, and high-performance computing where every millisecond counts.

Interpreted Languages: The Dynamic Translators

Interpreted languages, on the other hand, don't create a separate executable upfront. Instead, when you run a program written in an interpreted language, an interpreter program reads your source code line by line (or in small chunks) and translates it into machine instructions on the fly. It's a dynamic, immediate translation that happens every time the program executes.

- Key Characteristic: Requires an intermediary translation layer (the interpreter) to run. The source code itself is often what gets distributed.

- Examples: Python, Ruby, PHP, JavaScript. These are popular for web development, scripting, data science, and applications where rapid development and flexibility are paramount.

Language vs. Implementation: A Crucial Distinction

It's vital to understand that a programming language itself isn't inherently "compiled" or "interpreted." Instead, it's the implementation of that language that dictates its execution strategy.

Take Python, for instance. It's often called an "interpreted language," but the standard CPython implementation first compiles your Python code into an intermediate format called bytecode. This bytecode is then interpreted by the Python Virtual Machine (PVM). Similarly, Java and C# also compile their source code into bytecode (Java bytecode and CIL/MSIL, respectively), which then runs on a Virtual Machine (JVM and .NET CLR). These bytecode systems offer a hybrid approach, marrying some compilation benefits with platform independence.

This distinction highlights a modern trend: many languages leverage both compilation and interpretation, sometimes even compiling code down to native machine code during execution for peak performance.

Deconstructing Compilation: The Assembly Line for Your Code

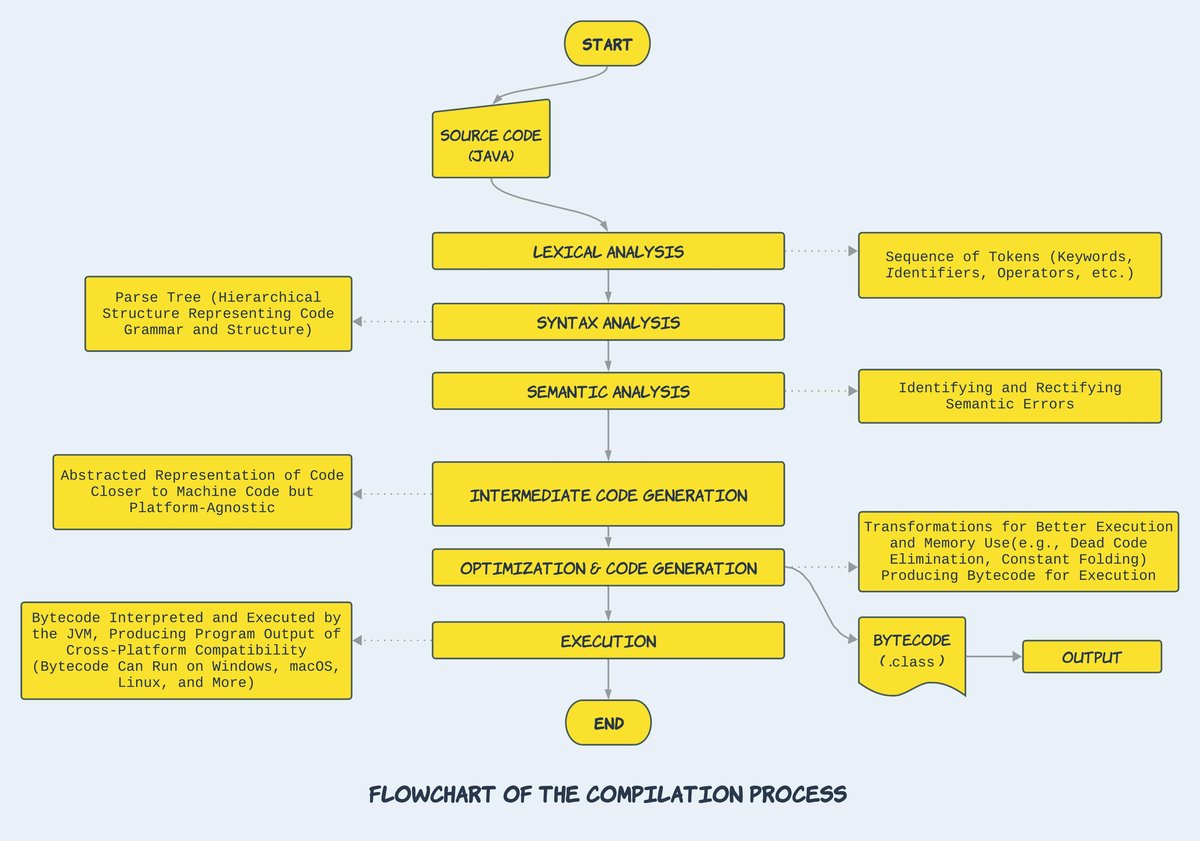

The compilation process is a sophisticated multi-stage journey, transforming abstract human-readable logic into highly optimized, machine-specific instructions. It's like a finely tuned assembly line, ensuring every component is perfect before the final product rolls out.

Here’s a simplified breakdown of the core steps:

- Parsing: The compiler's first job is to read your source code file, character by character. It then tokenizes this stream of characters, recognizing keywords, identifiers, operators, and literals. This stream of tokens is then structured into an Abstract Syntax Tree (AST) – a hierarchical representation of your code's structure, much like a grammatical parse tree for a sentence.

- Analysis: With the AST in hand, the compiler performs various checks and gathers information. This includes:

- Lexical Analysis: Verifying that tokens are valid (e.g., no misspelled keywords).

- Syntax Analysis: Ensuring the code follows the language's grammatical rules.

- Semantic Analysis: Checking for meaning and consistency, like type checking (are you trying to add a string to an integer?). It also resolves symbols, ensuring that variables and functions are declared correctly before use.

- Code Generation: This is where the magic happens. The compiler translates the analyzed AST into a lower-level, machine-readable format. This could be:

- Assembly Language: A human-readable representation of machine code, which then needs a separate assembler to convert it into actual binary machine code.

- Machine Code (Native Code): Direct binary instructions specific to the target CPU architecture (e.g., x86, ARM).

- Bytecode: An intermediate, platform-independent code that will later be interpreted or further compiled by a Virtual Machine.

- Linking: Most programs rely on pre-existing code, either from the language's standard library or external third-party libraries. The linker combines the machine code generated from your program with the machine code from these libraries, resolving references and ensuring all pieces fit together to form a complete, executable program.

- Optimization: This is a crucial step where the compiler acts as a performance engineer. It applies sophisticated techniques to make the generated code run faster, consume less memory, or both. Common optimizations include:

- Dead Code Removal: Eliminating code that can never be reached or executed.

- Constant Folding: Replacing expressions with their calculated values at compile time (e.g.,

2 + 3becomes5). - Loop Unrolling: Replicating the body of a loop multiple times to reduce loop overhead for small, fixed-iteration loops.

- Register Allocation: Efficiently assigning variables to fast CPU registers instead of slower memory.

The output of this entire process is a finely tuned machine code executable, perfectly tailored to its target hardware, ready to run without any further translation. This upfront effort is a significant reason compiled code often enjoys a performance edge. If you're looking for unlocking peak code performance from your applications, understanding this process is key.

The Interpreter's Dynamic Dance

While compilation is a heavy-duty, one-time transformation, interpretation is a lightweight, continuous dance. An interpreter doesn't build a complete executable; instead, it performs translation and execution in immediate, small bursts.

Here’s how an interpreter typically works:

- Read and Parse: The interpreter reads a small chunk of your source code – often a single line, a statement, or a block. It performs a quick parse to understand the syntax and basic structure of that segment.

- Execute Immediately: Without waiting to process the entire program, the interpreter immediately translates that parsed chunk into lower-level bytecodes or direct machine instructions. It then executes these instructions, processing any results.

- Flow Control: Based on the execution of the current chunk (e.g., conditional statements, function calls), the interpreter determines the next segment of code to read and execute. This cycle repeats until the program finishes or encounters an error.

This dynamic, on-the-fly approach means interpreted programs are always running through this translation layer. Every time you launch a Python script or load a JavaScript page, the interpreter is actively working to translate and execute your code in real-time. This flexibility is powerful, but it comes with a cost regarding raw execution speed.

The Best of Both Worlds: Just-in-Time (JIT) Compilation

Modern computing rarely fits neatly into "compiled" or "interpreted" boxes anymore. The advent of Just-in-Time (JIT) Compilation has significantly blurred these lines, offering a powerful hybrid approach that combines the flexibility of interpretation with the speed of compilation.

JIT compilers are used extensively in environments like Java's JVM, .NET's CLR, and modern JavaScript engines (like V8 in Chrome). They work by dynamically compiling "hot spots" – pieces of code that are executed frequently – the first time they run.

Here’s how JITs turbocharge performance:

- Runtime Profiling: JIT compilers constantly monitor your program's execution, identifying code paths that are run repeatedly (e.g., loops, frequently called functions).

- Dynamic Compilation: When a "hot spot" is detected, the JIT compiler steps in. Instead of interpreting that code every time, it compiles it directly into highly optimized native machine code. This compiled version is then cached and used for all subsequent executions of that hot path.

- Adaptive Optimization: JITs don't stop there. They can continuously profile the running program, even recompiling previously optimized code if new runtime information suggests a better optimization strategy. For example, if a function initially received integer inputs but later starts getting floating-point numbers, the JIT might de-optimize and recompile it for efficiency.

- Techniques for Speed:

- Tracing JITs: Focus on compiling long-running traces or sequences of operations.

- Inline Caching: Stores information about the types of arguments passed to functions, allowing for faster, direct calls in subsequent executions.

The impact of JIT compilation is profound. It allows languages traditionally labeled "interpreted" to achieve near-native performance for computationally intensive tasks. For example, a simple prime number calculator written in Python, when run through a highly optimized JIT, can achieve speedups of 10-100x, closing the performance gap significantly with compiled languages like C. This makes it easier to boost developer productivity without sacrificing speed.

Why Speed Matters: A Performance Deep Dive

When it comes to raw execution speed, compiled languages often have a distinct advantage. This isn't just because of the upfront translation; several fundamental differences contribute to their ability to squeeze maximum performance out of hardware.

Compiled Language Advantages (Performance Focus):

- Static Typing: Many compiled languages (like C++, Java, Go, Rust) are statically typed. This means variable types are known at compile time.

- Benefits: The compiler can allocate tighter memory layouts, optimize CPU register allocation, and generate specialized instructions, knowing exactly what kind of data it's dealing with. It also eliminates the need for runtime type checks, which can be a significant overhead in dynamically typed interpreted languages.

- Memory Usage Optimization: Compilers have a global view of the program. This allows for superior optimization of memory allocations, especially in performance-critical code paths.

- Benefits: Reducing unnecessary memory allocations directly translates to less work for garbage collection systems, leading to lower overhead and more consistent performance.

- Advanced Loop Optimization: Compilers can perform deep analysis of loop bodies.

- Benefits: Techniques like loop unrolling (copying the loop body multiple times to reduce branch penalties and loop overhead), vectorization (performing operations on multiple data items simultaneously), and intelligent scheduling result in vastly more efficient execution than the repeated dispatch checks an interpreter must perform for each iteration.

- Lower Function Call Overhead: In compiled code, function calls are typically a direct jump to a memory address, often with arguments passed directly in CPU registers.

- Benefits: This is incredibly fast. Interpreters, by contrast, might need to perform dictionary lookups, dynamic dispatch, or resolve method calls at runtime, adding significant overhead to each function invocation.

- Hardware-Specific Tuning: Compilers can be configured to target specific CPU architectures and instruction sets, leveraging specialized hardware features for maximum efficiency.

These advantages collectively explain why operating systems, device drivers, high-performance computing applications, and demanding video games are almost exclusively built with compiled languages. The upfront compilation time is a worthy trade-off for the unparalleled runtime speed. If you want to explore modern software architecture, you'll find these principles at its core.

Beyond Raw Speed: The Interpreted Edge

While compiled languages often win the raw speed race, interpreted languages offer a compelling set of advantages that have made them indispensable in modern software development. These benefits often prioritize developer experience, flexibility, and broader accessibility.

Advantages of Interpreted Languages:

- Faster Development Cycles: The absence of a separate compile, build, and link step drastically accelerates the code-test-debug iteration loop.

- Benefit: Developers can write code, save it, and immediately run it to see the results. This instant feedback fosters intuitive IDE workflows, interactive debugging, and rapid prototyping, significantly boosting developer productivity.

- Cross-Platform Portability: Languages that rely on bytecode and virtual machines (like Python, Java, JavaScript, C#) can often run on any operating system or hardware architecture that has a compatible interpreter or VM.

- Benefit: Write once, run anywhere. This simplifies deployment and broadens the reach of applications without needing to recompile for each target platform, making it ideal for achieving true cross-platform compatibility.

- Dynamic Features and Flexibility: Interpreted environments often support powerful dynamic features that are difficult or impossible in strictly compiled languages.

- Benefit: This includes dynamic typing (variable types determined at runtime), runtime evaluation of code strings, introspection (examining objects and code at runtime), and "monkey patching" (modifying code or behavior at runtime). These features enable highly flexible programming metaphors and make languages incredibly versatile for scripting and adaptive systems. You can dive deeper into programming paradigms by looking into these dynamic features.

- Enhanced Memory Safety: Many interpreted languages come with automatic memory management through garbage collection.

- Benefit: This frees developers from manually allocating and deallocating memory, preventing common and dangerous classes of errors like double-frees, memory leaks, and buffer overflows that are prevalent in languages like C/C++. This leads to more robust and secure applications.

For many applications—especially those involving web services, data manipulation, automation, or user interfaces where human interaction is the bottleneck—developer velocity and ease of deployment often outweigh the need for every last drop of CPU performance.

A Historical Lens: Pioneers and Paradigms

The journey of code compilation and interpretation is deeply intertwined with the history of computing itself. Early pioneers laid the groundwork for the tools and languages we use today:

- John Backus and IBM (1957): Revolutionized programming with the creation of the FORTRAN compiler. This marked a pivotal moment, as it was the first widely successful high-level programming language compiler, allowing engineers and scientists to write programs in a more abstract way than assembly language.

- John McCarthy (1958): Invented Lisp, one of the earliest high-level programming languages, which famously embraced an interpreted paradigm, emphasizing symbolic computation and dynamic evaluation.

- Niklaus Wirth: A towering figure in compiler design, he built influential compilers for languages like Pascal, and later designed entire systems around languages like Modula and Oberon, championing structured programming and efficient compilation.

- Guido Van Rossum (1991): Gave the world Python, a language celebrated for its readability and interpreted nature, rapidly becoming a favorite for web development, scripting, and data science.

- Brendan Eich (1995): Created JavaScript in just ten days, initially conceived as a client-side scripting language for web browsers. Its interpreted, dynamic nature was central to its rapid adoption.

- Anders Hejlsberg: A key architect behind iconic compilers and languages, including Delphi/Turbo Pascal and, later, C# (which leans heavily on JIT compilation within the .NET ecosystem).

These figures, among many others, shaped our understanding of how to translate human ideas into machine actions, continually pushing the boundaries of what's possible in software.

Making the Call: When to Choose What

The choice between a compiled or interpreted language is rarely absolute, and as we've seen, many modern environments blend the two approaches. The "right" decision depends heavily on your project's specific requirements, constraints, and priorities.

Lean Towards Compiled Languages If:

- Maximum Runtime Performance is Critical: If your application is CPU-bound, requires extremely low latency (e.g., trading systems, real-time control), or needs to squeeze every ounce of performance from the hardware (e.g., AAA games, operating systems), a compiled language is usually the best choice.

- Hardware Resources are Scarce: For embedded systems, IoT devices, or highly constrained environments where memory and processing power are limited, compiled code's efficiency and smaller footprint are invaluable.

- Code Stability After Release: If your code base is expected to be relatively stable after deployment, justifying the upfront compilation time, compiled languages shine.

- Strong Type Guarantees are Desired: For large, complex systems where type errors can be catastrophic, the compile-time type checking of languages like C++ or Rust provides significant safety and helps catch bugs early.

Prefer Interpreted Languages When:

- Developer Productivity Matters Most: For rapid prototyping, web development, scripting, or applications where getting features out quickly is the top priority, the fast iteration cycles of interpreted languages are unmatched.

- Cross-Platform Support is Needed "Out of the Gate": If your application needs to run on Windows, macOS, and Linux without significant platform-specific recompilation, a language with a robust virtual machine (Java, Python, C#, JavaScript) simplifies deployment immensely.

- Dynamic Features are Useful: For applications requiring flexibility, runtime code modification, or meta-programming, dynamically typed and interpreted languages offer unparalleled capabilities.

- Performance is Not the Primary Factor: For most business applications, web services, or desktop tools, the performance difference between a well-written interpreted program (especially with JIT) and a compiled one is often negligible in the face of network latency or user interaction times.

The Real World: A Hybrid Landscape

In practice, most real-world applications leverage a mix of both. A high-performance video game might have its core engine written in C++ (compiled) but use Python or Lua (interpreted) for scripting game logic, UI, and modding capabilities. Web browsers themselves are massive compiled applications (often C++), but they house incredibly sophisticated JavaScript (interpreted with JIT) engines to run interactive web pages.

This pragmatic approach allows developers to choose the best tool for each specific job, optimizing for performance where it's absolutely crucial, and for developer velocity and flexibility everywhere else. When you explore our complete guide, you'll see how these choices ripple through the entire software development lifecycle.

Common Questions & Misconceptions

Let's clear up some common points of confusion regarding compilation and interpretation.

Q: Is "fast" always better?

A: Not necessarily. While raw execution speed is a benefit of compiled languages, "fast" in software development can also mean fast development, fast deployment, or fast iteration. Interpreted languages often excel in these areas. The "best" choice is the one that meets your project's overall goals, balancing performance with other factors like developer time, maintenance, and flexibility.

Q: Does JIT compilation make interpreted languages as fast as compiled ones?

A: JIT compilation can achieve near-parity with compiled languages for specific "hot" code paths, often dramatically improving performance. However, there's usually still an overhead for the JIT to profile, compile, and manage code at runtime, meaning compiled languages often retain an edge in absolute peak performance for computationally intensive, long-running tasks. Plus, the startup time for a JIT-compiled application might be longer than a purely compiled one because of the initial compilation phase.

Q: Can a language be both compiled and interpreted?

A: Yes, absolutely! As discussed, the distinction lies in the implementation, not the language itself. Python, Java, and C# are great examples. They typically involve an initial compilation to bytecode, which is then interpreted or JIT-compiled by a virtual machine. Even traditionally compiled languages like C can have interpreters (though they're less common for production use).

Q: Do interpreted languages always use more memory?

A: Generally, yes. Interpreters themselves require memory to run, and they often carry around the source code or an intermediate representation of it, in addition to the program's data. Dynamically typed languages also tend to use more memory per variable because they need to store type information alongside the value, whereas compiled languages can often pack data more tightly. However, modern interpreted environments are highly optimized, and this difference might not be significant for many applications.

Charting Your Course: Mastering Program Execution

The dichotomy of code compilation and interpretation is more than just a technical detail; it's a foundational concept that shapes the very landscape of software development. From the earliest days of FORTRAN to the dynamic web of JavaScript, every line of code written has traversed some form of this translation journey.

By understanding the strengths and weaknesses of each approach, and particularly the transformative power of Just-in-Time compilation, you're not just gaining knowledge – you're gaining the insight to architect more efficient, more robust, and more successful software. Whether you're optimizing for nanoseconds in a high-frequency trading system or crafting a seamless user experience for a global web application, the choices you make in how your code is executed will fundamentally drive your program's speed and overall impact. Armed with this understanding, you're better equipped to select the right tools for your projects and truly master the art of bringing software to life.