Imagine a finely tuned engine: every part works in concert, but what happens when a critical component suddenly fails? Without robust safeguards, the entire machine grinds to a halt, leaving users stranded and trust eroded. In the world of software, Error Handling & Exception Management serves as that crucial immune system, allowing your applications to gracefully navigate the unexpected, prevent catastrophic failures, and maintain user confidence. It's the hallmark of professional development, distinguishing amateur code from resilient, production-ready systems.

It’s not just about fixing bugs; it’s about anticipating the countless ways things can go wrong—from a network timeout silently disrupting a critical operation to a user unwittingly providing invalid input. Implementing thoughtful error handling ensures your software can absorb these shocks, recover gracefully, or at the very least, fail predictably and informatively, rather than crashing into an abyss.

At a Glance: Building Unbreakable Software

- Anticipate the Unexpected: Design your applications to handle common and uncommon errors gracefully.

- Understand Error Types: Differentiate between syntax (compile-time), runtime (execution), and logic (incorrect output) errors to apply the right solutions.

- Master

try-catch-finally: Use these blocks strategically to contain risky operations, manage exceptions, and ensure resource cleanup. - Log Everything (Wisely): Capture critical error details with context for debugging, but avoid leaking sensitive information.

- Embrace Resilience Patterns: Proactively prevent cascading failures with tools like circuit breakers and retry mechanisms.

- Test Your Defenses: Deliberately break your code to verify that error handling paths work as intended.

- Prioritize Performance & Security: Minimize the performance overhead of exceptions and prevent error messages from exposing sensitive data.

- Categorize for Clarity: Group errors (business, technical, user) to facilitate targeted handling and faster resolution.

Why Your Software Needs an Immune System: The Crucial Role of Error Handling

Every piece of software operates within an ecosystem of users, networks, databases, and other services. This environment is inherently unpredictable. A database might go offline, a file might be corrupted, or a user might enter gibberish where you expect a valid email address. These "unexpected conditions" are not necessarily flaws in your code, but rather external realities that demand a robust response.

Good error handling isn't just about catching errors; it’s about ensuring an application remains stable, provides a consistent user experience, and helps developers quickly diagnose and resolve issues. Without it, even minor hiccups can lead to cascading failures, data corruption, and a complete breakdown of trust.

The Many Faces of Failure: Understanding Different Error Types

Not all errors are created equal, and understanding their distinctions is the first step toward effective management.

- Syntax Errors: These are the easiest to spot and resolve. They occur when your code violates the grammatical rules of the programming language—think forgetting a semicolon or misspelling a keyword. Your compiler or interpreter will usually flag these immediately, preventing the code from running until they’re fixed.

- Runtime Errors: These errors emerge during the program's execution, often due to factors outside your code's direct control. Examples include trying to access a file that doesn't exist, connecting to a database that's offline, or encountering a network timeout. While your code might be syntactically perfect, the environment it operates in presents a challenge. These are the primary targets for

try-catchblocks. - Logic Errors: The most insidious and dangerous of the bunch, logic errors allow your code to run without crashing or overt failures, but it produces incorrect results or corrupts data. Perhaps your calculation for a customer's total ends up 10% off, or your data synchronization process introduces subtle inconsistencies. These errors cannot be caught by

try-catchblocks because, from the system's perspective, everything is functioning "normally." Identifying and fixing logic errors requires meticulous testing, comprehensive code reviews, and deep understanding of the business requirements.

The Anatomy of a Graceful Failure: Core Mechanisms of Exception Handling

When a runtime error occurs, the standard flow of your program is interrupted. This "exceptional event" needs a structured way to be communicated and dealt with. Modern programming languages provide a powerful set of tools for this.

- Throwing an Exception: This is how your code, or a library it uses, signals that something has gone wrong. When an exception is "thrown," normal operations immediately cease. It's like an alarm bell ringing, alerting the system that an exceptional event requires attention. Crucially, exceptions should be reserved for genuine, unexpected problems—situations where the normal execution path cannot continue—rather than for routine conditional logic.

- Exception Objects: When an exception is thrown, it's not just a vague signal; it's a rich object carrying detailed information about what went wrong. This object acts as a forensic report, including a clear message describing the issue, relevant context about the system's state at the time, an error code for programmatic identification, and a stack trace that pinpoints exactly where in the code the exception originated. The quality of this information is paramount for effective debugging and recovery.

- Catch Blocks: These are your application's designated responders. When an exception is thrown, the system searches for a suitable

catchblock that is equipped to handle that specific type of exception. Once found, thecatchblock receives the exception object and can then decide how to respond: log the error, attempt to fix the problem, notify a user, retry an operation, or escalate the issue further up the call stack.

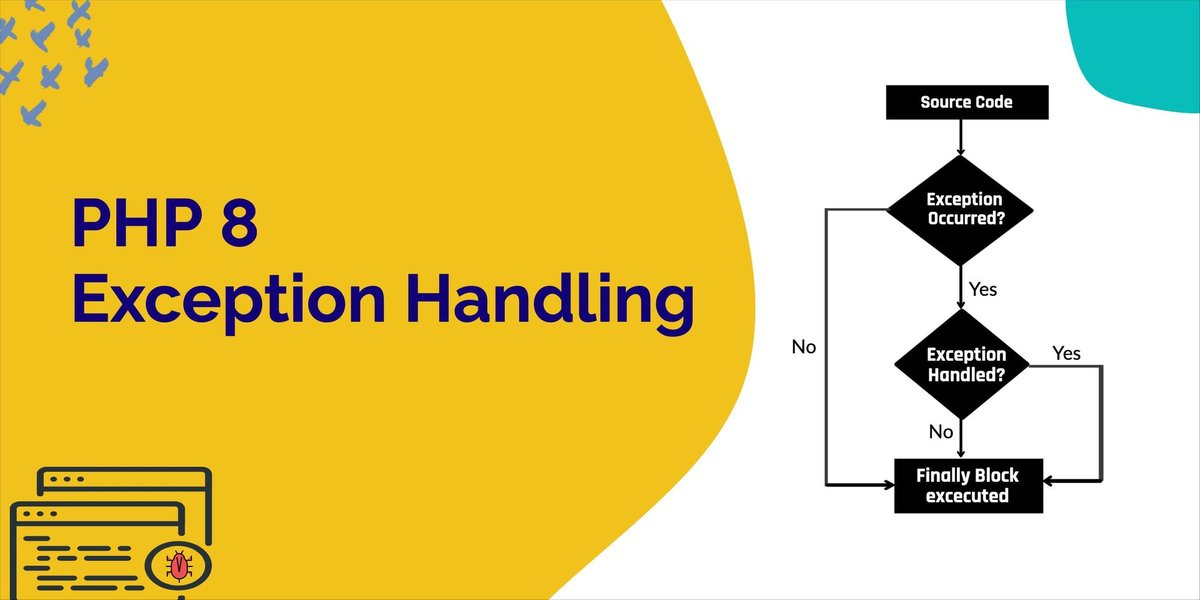

try-catch-finally: Your Essential Safety Net

The try-catch block is the fundamental construct for handling exceptions. It acts as a protective wrapper around code segments that are prone to external failures.

- The

tryblock contains the code that might throw an exception. It's where you put your risky operations. - If an exception occurs within the

tryblock, the program immediately jumps to thecatchblock, which is designed to handle specific exception types. You can have multiplecatchblocks to tailor responses to different kinds of exceptions (e.g., one forFileNotFoundException, another forDatabaseConnectionException). This allows for highly specific and effective recovery strategies. - The

finallyblock, if present, always executes, regardless of whether an exception was thrown or caught. This makes it ideal for cleanup operations, such as closing file handles, database connections, or releasing system resources, ensuring that your application doesn't leak resources even when things go awry.

Remember,try-catchblocks should be reserved for operations genuinely susceptible to failure, not wrapped around every line of code. Overuse can make your code harder to read and may even hide logic errors if exceptions are used for routine control flow.

Crafting Robust Code: Principles for Professional Exception Management

Effective exception handling goes beyond syntax; it's a strategic approach deeply ingrained in your development philosophy.

- Be Specific, Not Generic: Always strive to catch specific exceptions (

IOException,SQLException) rather than generic ones (Exception,Error). Catching a broadExceptioncan hide important details and prevent you from implementing tailored recovery actions. Only catch generic exceptions at the highest architectural boundaries, where the intent is simply to log and potentially shut down gracefully. - Never Leave

catchBlocks Empty: A silent failure is arguably worse than a crash. An emptycatchblock means an exception occurred, but your application swallowed it without acknowledging, logging, or addressing it. This creates insidious bugs that are nearly impossible to trace. At a minimum, log the exception. - Log with Context, Avoid Trivialities: When you log an exception, ensure the log message includes enough context to understand the problem: the full stack trace, relevant input parameters, the user involved (if applicable), and any other state variables. Conversely, avoid logging trivial errors that don't impact functionality or indicate a problem that needs developer attention.

- Fail Fast When Recovery is Futile: If an error makes it impossible for your application to continue meaningful operation (e.g., a critical database connection is lost and cannot be re-established), don't try to limp along. Failing fast, with clear error messages and logging, is often the best course of action. This prevents further data corruption or incorrect results and makes the problem immediately apparent.

Don't Just Catch: What to Do (and Not Do) in a catch Block

A catch block is a decision point. What you do inside it defines your application's resilience.

- Do:

- Log the exception: Crucial for debugging and monitoring.

- Provide a graceful user experience: Display a user-friendly error message.

- Attempt recovery: Retry the operation, use a fallback mechanism, or notify an administrator.

- Clean up resources: Use

finallyortry-with-resources(Java) /using(C#) for this, but if that's not possible, ensure cleanup here. - Re-throw if partially handled: If you can perform some cleanup but the error still needs higher-level attention, re-throw the original exception or a new, more specific one.

- Don't:

- Swallow the exception: Never leave a

catchblock empty. - Ignore the exception: Even if you can't fix it, acknowledge it.

- Display raw technical error messages to users: This leaks sensitive information and confuses users.

- Use exceptions for normal control flow: Exceptions are for exceptional circumstances.

Strategic Placement: Where to Catch What

The optimal place to handle an exception depends entirely on its nature and the architectural layer where it originates. Thoughtful placement minimizes redundant error handling and ensures issues are addressed at the most appropriate level.

- Technical Errors (e.g., database connection issues, file I/O problems): These are best handled at service boundaries or within infrastructure layers. A data access layer might attempt a retry, or escalate an unrecoverable database error to a higher business service.

- Business Logic Errors (e.g., "insufficient funds," "invalid order status"): These should be handled at the domain layer. Here, the application understands the business context and can return meaningful business-level error messages or codes, rather than technical exceptions.

- User Input Errors (e.g., incorrect date format, missing required field): Catch these primarily at the presentation layer (frontend or API gateway). This allows for immediate feedback to the user, preventing invalid data from even reaching your backend logic.

- System-Wide Errors: For unhandled exceptions that propagate through all layers, global exception handlers act as the ultimate safety net. These catch anything that slips through, preventing crashes, logging critical details, notifying administrators, and presenting a generic, graceful error message to the end-user. This ensures that even when something truly unexpected happens, your application doesn't just vanish.

Understanding the Flow: Error Propagation and Stack Unwinding

When an exception is thrown, it doesn't just stop the current line of code. It initiates a complex but orderly process to find a suitable handler.

Stack unwinding is the methodical process where the runtime system destroys local variables and calls destructors (in languages like C++) for objects in the call stack as an exception propagates. This ensures that resources are released and memory is cleaned up, even if the normal execution path is interrupted.

Exception bubbling describes how exceptions escalate up the call stack. When an exception is thrown in a method, the runtime looks for a catch block within that method. If none is found, the exception "bubbles up" to the calling method. This process continues, unwinding the stack frame by frame, until a suitable catch block is found. This mechanism is powerful because it allows low-level errors (like a database connection failure in a utility method) to be handled at higher architectural boundaries (like a business service that knows how to retry or use a fallback).

Beyond the Basics: Advanced Strategies for Unbreakable Systems

True resilience goes beyond merely catching errors; it involves proactive measures and continuous improvement.

Proactive Defenses: Resilience Patterns in Action

Some errors are temporary glitches, while others indicate a deeper problem. Resilience patterns help your application respond intelligently.

- Circuit Breakers: Imagine an electrical circuit breaker protecting your home. If a service you depend on (like an external API) repeatedly fails, a circuit breaker pattern will temporarily "trip," preventing your application from making further calls to that failing service. This stops cascading failures, gives the failing service time to recover, and allows your application to use a fallback mechanism or fail fast.

- Retry Mechanisms with Exponential Backoff: For transient errors (e.g., a momentary network hiccup, a database lock), simply retrying the operation might solve the problem. Exponential backoff is a smart retry strategy where the application waits progressively longer between retry attempts. This prevents overwhelming a struggling service with continuous retries and allows it time to recover.

- Bulkhead Patterns: Borrowing from shipbuilding, where bulkheads isolate compartments to prevent a single leak from sinking the entire ship, this pattern isolates different parts of your application or service calls. If one service starts to fail or consume too many resources, the bulkhead pattern ensures that only that specific compartment is affected, preventing widespread system impact.

Verifying Your Safeguards: Testing Exception Handling

It's not enough to implement error handling; you must prove it works.

- Deliberately breaking code: Write unit and integration tests that specifically trigger expected exceptions. Verify that your

catchblocks execute, logs are generated correctly, and the application responds as intended (e.g., a graceful error message is displayed). - Chaos Engineering: For highly resilient systems, consider chaos engineering. This involves intentionally injecting failures into a production or production-like environment (e.g., randomly killing services, introducing network latency) to observe how the system behaves and identify weaknesses in your error handling and resilience strategies. This helps build confidence in your software's ability to withstand real-world chaos.

The Cost of Failure: Performance and Security Considerations

While essential, exception handling isn't without its costs.

- Performance: Throwing and catching exceptions can be an expensive operation, involving stack unwinding and object creation. In high-frequency code paths, excessive use of exceptions for routine control flow can introduce noticeable performance overhead.

- Minimize frequency: Use input validation and precondition checking to prevent exceptions before they happen.

- Return codes/Optional types: For expected errors (e.g., a

findUsermethod not finding a user), returning a specific error code, a boolean, or anOptional/Maybetype can be more performant than throwing an exception. - Cache exception objects: In rare, highly performance-critical scenarios, you might cache and reuse exception objects to reduce allocation overhead.

- Security: Exception messages, especially the raw stack traces, can inadvertently leak sensitive information about your application's internal structure, file paths, database queries, and even API keys. This information can be invaluable to an attacker.

- Layered error reporting: Implement a clear distinction: detailed error messages and stack traces should be for developers and administrators only (e.g., logged internally). For end-users, present sanitized, generic, and user-friendly messages that don't reveal internal workings.

Categorizing Chaos: Making Sense of Different Error Types

To effectively handle errors, you need a system to classify them. This helps in identifying root causes, developing targeted handling strategies, and continuously improving your application's robustness.

- Business Logic Errors: These are flaws within the application's core logic or data inconsistencies that violate business rules. Examples include an invalid calculation in an e-commerce platform, an attempt to process an order for an out-of-stock item, or a user trying to access data they don't have permission for based on their role. Handling these often involves specific domain exceptions and user-facing messages explaining the business rule violation.

- Technical Errors: These relate to underlying system aspects. Think database connectivity failures, network timeouts, file system access denied, or hardware malfunctions. These typically occur at the infrastructure or service layer and often require retries, fallback mechanisms, or escalating to system administrators.

- User Errors: These stem directly from unintended user interaction, such as providing invalid input (e.g., text where a number is expected), attempting an action without the necessary permissions, or trying to operate on a non-existent resource. These errors are best caught and communicated at the presentation layer to guide the user towards correct interaction.

When to Design Your Own: The Power of Custom Exceptions

While standard library exceptions cover many common scenarios, creating custom exceptions allows you to model specific error conditions unique to your application's domain.

- Improved readability and maintainability:

InvalidOrderStateExceptionis far more descriptive than a genericIllegalArgumentException. - Better, more targeted handling: With custom exceptions,

catchblocks can become highly specific, allowing for precise recovery actions or user feedback. - Enhanced error information: Your custom exception objects can include domain-specific properties like an

errorCode, a more descriptivemessage, or even relevant business data to aid in debugging.

Best practices for custom exceptions include inheriting from a base exception class (e.g.,RuntimeExceptionin Java,Exceptionin C#), providing meaningful error messages, and incorporating relevant error codes.

Leveraging Frameworks: Building on Giants for Consistent Handling

Many robust applications don't reinvent the wheel for error handling. They rely on established exception handling frameworks and libraries that provide a structured, consistent, and often more efficient approach.

Frameworks like Spring Framework for Java, Polly for .NET, or Tenacity for Python offer:

- Structured approaches: Standardized ways to define, throw, and catch exceptions across your codebase.

- Pre-built mechanisms: Often include out-of-the-box support for global exception handling, retry logic, circuit breakers, and more.

- Logging and reporting integration: Seamlessly tie into existing logging and monitoring systems.

- Customization options: Allow you to extend their capabilities with your domain-specific error handling logic.

Using these frameworks simplifies implementation, improves consistency across different modules, and enhances the overall quality of your error information. They allow you to focus on your core business logic while providing a solid foundation for resilience, helping you to Explore our Does Then hub and understand how larger systems are built.

Putting It All Together: Implementing Error Handling in Your Codebase

Translating theory into practice involves conscious design decisions at every stage of development.

- Identify Risky Operations: Explicitly mark or document parts of your code that interact with external systems, user input, or might lead to business rule violations. These are your prime candidates for

try-catchblocks. - Use

try-catchBlocks Judiciously: Wrap only the code that can genuinely throw an exception. Avoid largetryblocks that obscure the source of an error. - Handle Specific Exceptions First: Always prioritize catching the most specific exception types relevant to your code.

- Keep Exception Handling Code Separate: Your

catchblocks should ideally contain only the logic necessary to handle the exception. Avoid intermingling it with your main application logic, which can make code harder to read and debug. - Utilize

finallyfor Cleanup: Ensure critical resources are always released.

Language Deep Dive: Specific Best Practices

While the core principles are universal, each language has its nuances.

- Java:

- Checked vs. Unchecked Exceptions: Java differentiates between checked exceptions (which must be caught or declared to be thrown) for recoverable errors and unchecked exceptions (like

RuntimeException) for programming errors. Use checked exceptions for scenarios where the caller can realistically recover, and unchecked for unrecoverable bugs. try-with-resources: For automatic resource closure (e.g., streams, database connections),try-with-resourcesautomatically ensures that resources implementingAutoCloseableare closed, even if an exception occurs.- C#:

usingstatement: Similar to Java'stry-with-resources, theusingstatement ensures proper disposal of objects that implement theIDisposableinterface, especially for unmanaged resources.- Exception Filters: C# allows you to add a

whenclause to yourcatchblocks, providing a powerful way to conditionally catch exceptions based on specific criteria without catching and re-throwing. - Python:

try-except-finally: Python's equivalent totry-catch-finally. Theexceptblock can catch specific exception types.withstatement: Python'swithstatement, used with context managers, is the idiomatic way to handle resource disposal (e.g., files, locks) automatically, similar totry-with-resourcesin Java.

Your Burning Questions Answered: Error Handling FAQs

Let's demystify some common questions and clear up misconceptions.

Q: What's the difference between "exceptions" and "errors"?

A: In many languages (like Java), "Exceptions" represent recoverable conditions that your program can often handle gracefully (e.g., FileNotFoundException). "Errors," on the other hand, typically denote more serious, unrecoverable problems that might terminate the program (e.g., OutOfMemoryError). Exception handling primarily targets these recoverable scenarios.

Q: Should I catch specific exceptions or just a generic Exception?

A: Always prioritize catching specific exceptions. This allows you to implement tailored recovery logic for each distinct problem. Only use generic Exception catches at the highest application boundaries, where the goal is usually to log the unhandled error and possibly shut down gracefully, not to recover.

Q: Does exception handling impact performance? How can I minimize it?

A: Yes, throwing and catching exceptions can be more expensive than normal control flow. To minimize impact:

- Validate input: Prevent exceptions by checking preconditions before attempting operations.

- Use return codes/optional types: For expected "failure" scenarios (e.g.,

userNotFound), returning a special value (null,false, anOptionaltype) is often more efficient than throwing an exception. - Efficient logging: Log judiciously; excessive, high-volume logging can be a bottleneck.

- Don't use exceptions for normal control flow.

Q: What information should a custom exception include?

A: A custom exception should include an error code (for programmatic identification), a descriptive message (for developers/logs), and any relevant contextual data specific to your domain (e.g., the ID of the object that caused the error, the type of operation). Crucially, avoid including sensitive information like passwords or personally identifiable data.

Q: How do you handle errors in asynchronous operations?

A: Asynchronous error handling aligns with the concurrency model you're using.

- Promises/Futures: Errors propagate as promise rejections (JavaScript, Java

CompletableFuture). async/await: Use standardtry-catchblocks aroundawaitcalls.- Callbacks: Errors are typically passed as the first argument to the callback function.

Q: What are the best practices for logging exceptions?

A:

- Appropriate severity: Log

ERRORfor critical issues,WARNfor potential problems. - Include stack traces: Essential for pinpointing the exact location of the error.

- Provide context: Add relevant variables, user IDs, or request IDs.

- Structured logging: Use JSON or other structured formats for easier parsing by monitoring tools.

- No sensitive data: Ensure logs do not contain passwords, PII, or other confidential information.

Q: When should I re-throw an exception?

A: Re-throw an exception when yourcatchblock performs some necessary cleanup or logging, but cannot fully resolve the problem. By re-throwing, you allow the exception to propagate further up the call stack, enabling a higher-level component (which might have more context or resources) to handle it or initiate a more global recovery strategy.

Building Software That Stands the Test of Time

Mastering error handling and exception management is less about writing perfect code and more about building resilient systems. It’s an acknowledgment that software operates in an imperfect world, and a commitment to ensuring that imperfections don't lead to catastrophe. By strategically employing try-catch-finally, understanding error propagation, embracing resilience patterns, and rigorously testing your defenses, you don't just fix bugs—you engineer confidence. Your applications become more reliable, your users more trusting, and your development team more efficient in the face of the inevitable unexpected.