When you picture a robot assembling car parts or a spreadsheet automatically calculating quarterly totals, what you’re really witnessing is the power of looping & iteration mechanisms in action. These fundamental programming constructs are the unseen engines that automate repetitive tasks, transforming tedious, error-prone manual operations into seamless, efficient processes. Without them, most modern software would be impossible, and your coding life would be a frustrating cycle of copy-pasting the same lines of code.

Imagine needing to process a list of a thousand customer names, send an email to each, or repeatedly check a sensor for new data. Typing out instructions for each individual instance would be a colossal waste of time and an open invitation for mistakes. Looping mechanisms offer an elegant solution, allowing you to write instructions once and have them executed as many times as necessary, until a specific condition is met or every item in a collection has been handled. It’s about working smarter, not harder, enabling your code to scale from a handful of tasks to millions with the flick of a digital switch.

At a Glance: Looping & Iteration Essentials

- What it is: The process of repeatedly executing a block of code.

- Why it matters: Automates repetitive tasks, dramatically improves code efficiency, readability, and reduces manual errors.

- Core Components: Iteration (the act of repeating), and Iterables (the collections of items you might loop over).

- Main Types:

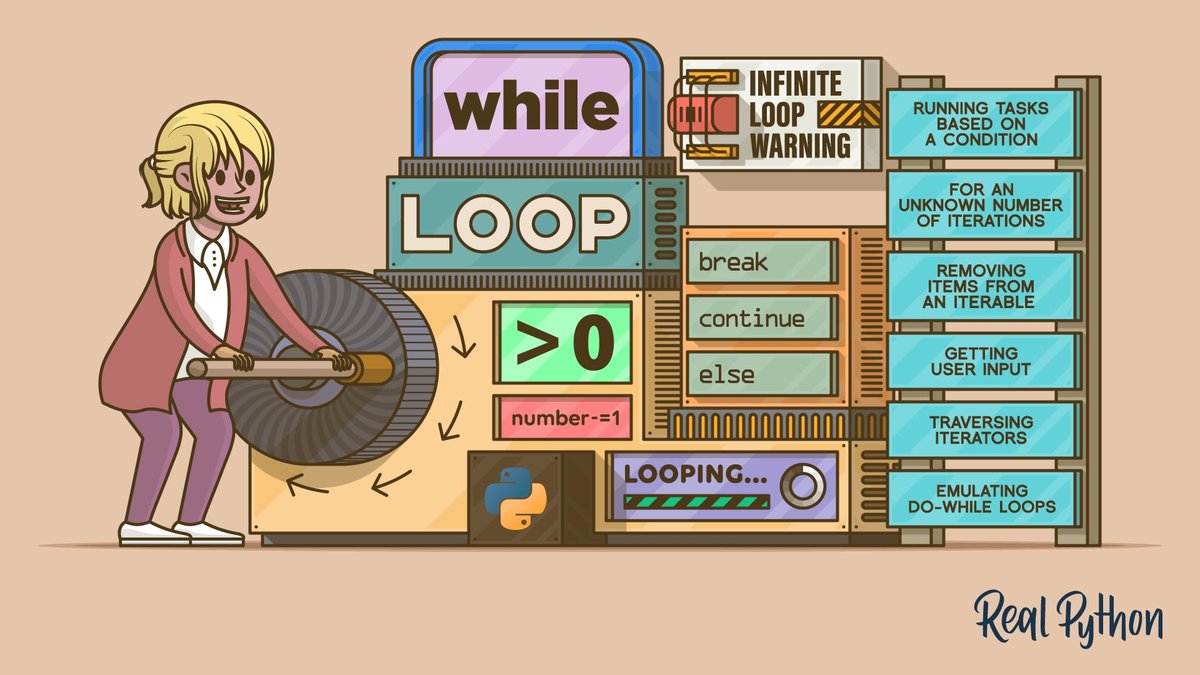

forloops (best for known repetitions or iterating over sequences) andwhileloops (ideal for conditional repetitions). - Control is Key:

breakstops a loop immediately;continueskips to the next iteration. - Watch Out For: Infinite loops, which can crash your program if not managed carefully.

The Undeniable Power of Repetition: Why Loops Are Indispensable

At its heart, programming is about giving computers instructions to solve problems. Many problems involve doing the same thing multiple times, perhaps with slightly different data each time. This is where iteration shines. Instead of manually writing print("Hello!") ten times, you write it once, embed it in a loop, and tell the loop to run ten times. Simple, elegant, and incredibly powerful.

Iteration control structures, universally known as loops, are what allow a statement or block of code to be executed repeatedly until a specific program state is reached. This could mean applying an operation to every element of a collection, waiting for a certain condition to be met, or simply running a set number of times. The keywords you'll commonly encounter are while, repeat, for, and do..until – each representing a slight variation in how that repetition is managed.

By automating these repetitive tasks, loops don't just save you keystrokes; they fundamentally improve:

- Code Efficiency: Tasks complete faster, especially with large datasets.

- Tidiness and Readability: Code becomes much shorter, cleaner, and easier to understand. Imagine scanning a script with 100 identical lines versus one clean loop.

- Error Reduction: Less manual repetition means fewer opportunities for typos or missed steps.

Before we dive into the specifics of different loop types, let's nail down two foundational concepts.

Iteration and Iterables: The Dynamic Duo

Iteration is simply the act of repeatedly executing a set of statements or a code block. When you "iterate," you're moving through a sequence or repeating an action. Loops are the programming structures that bring this concept to life.

Iterables are the unsung heroes of many iteration scenarios. These are objects whose elements can be accessed one by one during iteration. Think of them as containers that you can step through, piece by piece. In Python, for instance, lists (ordered collections of items) and strings (sequences of characters) are prime examples of iterables. When you loop through a list, you're iterating over its elements. When you loop through a string, you're iterating over its characters. Understanding different data structures like these is crucial for effective looping.

Decoding the for Loop: When You Know How Many Times

The for loop is your go-to mechanism when you know, or can easily determine, the number of repetitions needed. It's perfectly suited for iterating over a sequence of elements, whether that's a list, a string, a range of numbers, or any other iterable object. If your task is "do this for each item in this collection" or "do this for this many times," a for loop is likely the most straightforward solution.

How for Loops Get the Job Done

A for loop typically works by assigning each item in an iterable sequence to a temporary variable, one by one, and then executing its block of code using that variable. Once every item has been processed, the loop naturally terminates.

Let's look at some Python implementations, which beautifully illustrate the versatility of for loops:

1. Counting with range(): For a Known Number of Repetitions

When you need to repeat an action a specific number of times, range() is your friend. It generates a sequence of numbers, which the for loop then iterates over.

python

Printing numbers from 0 to 9

print("Counting from 0 to 9:")

for i in range(10): # range(10) generates numbers 0, 1, 2, ..., 9

print(i)

print("\nTen push-ups simulation:")

for pushup_count in range(1, 11): # range(start, stop) - stop is exclusive

print(f"Push-up number {pushup_count}!")

print("Great job, you completed 10 push-ups!")

In the first example, range(10) creates a sequence of numbers from 0 up to (but not including) 10. The for loop then assigns each of these numbers to i in turn, executing the print(i) statement for each.

2. Iterating with range(len()) and Indexing: When You Need the Position

Sometimes, you don't just need the item itself, but also its position (index) within the sequence. This is common when you need to modify elements in a list by their index or perform actions that depend on an element's order.

python

shopping_list = ["apples", "milk", "bread", "eggs", "juice"]

print("\nProcessing shopping list with indices:")

for index in range(len(shopping_list)): # len(shopping_list) is 5, so range(5) is 0,1,2,3,4

item = shopping_list[index]

print(f"Item {index + 1}: {item}")

You could also modify the list here, e.g., shopping_list[index] = item.upper()

Here, len(shopping_list) returns the number of items in the list (5). range(5) then provides the indices 0, 1, 2, 3, 4. The loop uses these indices to access each item from the shopping_list.

3. Direct Iteration: The Most Pythonic Way for Elements

Often, you simply need to access the elements of an iterable one by one, without caring about their index. This is the most straightforward and often preferred way to use for loops in Python.

python

cities = ["London", "Paris", "Tokyo", "New York"]

print("\nVisiting cities directly:")

for city in cities: # 'city' directly takes each element from 'cities'

print(f"Welcome to {city}!")

sentence = "Python is powerful!"

print("\nCharacters in a sentence:")

for char in sentence:

print(char, end=" ") # Using end=" " to print characters on one line

print()

In these examples, the loop directly assigns each city from the cities list or each char from the sentence string to the loop variable, making the code extremely readable and concise. This direct approach is often preferred because it's less prone to "off-by-one" errors that can sometimes creep in when manually managing indices.

Mastering the while Loop: When the Condition Drives Repetition

While for loops excel when you know the number of iterations or are traversing a collection, while loops are the champions of conditional repetition. You use a while loop to iterate over a sequence of elements as long as a specified condition remains true. The moment that condition becomes false, the loop stops.

Think of a while loop as a security guard who keeps checking an ID. As long as the ID is valid (condition is true), the person stays. The moment it's invalid (condition is false), they're out.

Building a while Loop: The Key Ingredients

A while loop requires careful setup to ensure it works correctly and, crucially, eventually terminates.

- Initialization: A variable (or variables) required for the loop's condition must be initialized before the loop begins. This variable's initial state determines if the loop runs even once.

- Condition: The

whilekeyword is followed by a condition (a Boolean expression) that evaluates toTrueorFalse. - Iteration Change: Inside the loop, you must include code that changes the variable(s) involved in the condition. Without this, the condition might never become false, leading to an infinite loop. The

+=(unary or increment) operator is commonly used to increment a counter variable, but the change could be anything that eventually makes the conditionFalse.

Let's illustrate with an example:

python

Counting up to 5 using a while loop

count = 1 # 1. Initialize the variable

print("Counting up using while loop:")

while count <= 5: # 2. The condition

print(count)

count += 1 # 3. Change the variable (increment by 1)

print("While loop finished.")

In this example:

countstarts at 1.- The loop continues as long as

countis less than or equal to 5. - Inside the loop,

countis printed, and thencount += 1increments it. - When

countbecomes 6, the condition6 <= 5isFalse, and the loop terminates.

PracticalwhileLoop Scenarios: - User Input Validation: Keep asking for input until a valid entry is provided.

python

password = ""

while password != "secret":

password = input("Enter the password: ")

if password != "secret":

print("Incorrect password. Try again.")

print("Access granted!") - Polling a Sensor/System: Repeatedly check for a status change.

python

sensor_reading = 0

Simulate a sensor reading that eventually goes above 10

import random

print("\nWaiting for sensor reading to exceed 10:")

while sensor_reading <= 10:

sensor_reading = random.randint(1, 15) # Simulate reading

print(f"Current sensor reading: {sensor_reading}")

if sensor_reading <= 10:

print("Still below threshold...")

print(f"Threshold exceeded! Final reading: {sensor_reading}")

The while...else Statement in Python

A unique feature in Python is the optional else statement that can be paired with a while loop. The code inside the else block executes only if the loop completes normally (i.e., its condition becomes false). It will not execute if the loop is terminated prematurely by a break statement. This can be useful for cleanup or final messages that only make sense if the entire loop ran its course.

python

Example of while...else

i = 0

while i < 3:

print(f"Inside loop: {i}")

i += 1

else:

print("Loop finished normally (i is now 3).")

Example where else is skipped due to break

j = 0

while j < 5:

print(f"Inside loop with break: {j}")

if j == 2:

print("Breaking loop at j=2.")

break # This prevents the 'else' block from executing

j += 1

else:

print("This 'else' block will NOT execute because of 'break'.")

This else block provides a neat way to handle different post-loop scenarios, often simplifying conditional logic that would otherwise require flags or additional checks after the loop.

Taking Control: break, continue, and the Infinite Loop Threat

Loops are powerful, but sometimes you need to exert more granular control over their execution. This is where break and continue statements come in handy. However, with great power comes the potential for pitfalls, like the dreaded infinite loop.

break: The Emergency Stop Button

The break statement provides an immediate exit from the current loop, regardless of its original terminating condition or remaining iterations. When break is encountered, the program immediately jumps to the code following the loop. It's like pressing an emergency stop button.

python

Using break in a for loop

print("Searching for 'grape' in a fruit list:")

fruits = ["apple", "banana", "cherry", "grape", "kiwi"]

for fruit in fruits:

print(f"Checking {fruit}...")

if fruit == "grape":

print("Found grape! Stopping search.")

break # Exit the loop immediately

print("Loop finished (or broke).")

Using break in a while loop

secret_number = 7

guess = 0

print("\nGuessing a number between 1 and 10:")

while True: # An intentional infinite loop, relying on 'break' to exit

guess = int(input("Enter your guess: "))

if guess == secret_number:

print("Congratulations! You guessed it.")

break

else:

print("Wrong guess. Try again.")

print("Game over!")

Notice how break in the while True example turns an otherwise infinite loop into a conditional one.

continue: Skipping to the Next Round

The continue statement allows you to skip the remaining code in the current iteration of the loop and proceed directly to the next iteration. It's useful when you want to bypass certain actions for specific elements or conditions, but still want the loop to complete its full course.

python

Using continue to skip even numbers

print("Printing odd numbers up to 10:")

for num in range(1, 11):

if num % 2 == 0: # If number is even

continue # Skip the rest of this iteration, go to the next num

print(num)

Using continue to process only positive numbers

data = [10, -5, 2, 0, -8, 15]

total_positive_sum = 0

print("\nSumming only positive numbers:")

for val in data:

if val <= 0:

print(f"Skipping non-positive value: {val}")

continue

total_positive_sum += val

print(f"Added {val}. Current sum: {total_positive_sum}")

print(f"Total sum of positive numbers: {total_positive_sum}")

The continue statement ensures that only positive values contribute to total_positive_sum, cleanly sidestepping the negative or zero values without stopping the loop entirely. For more complex decision-making within loops, you might want to understand conditional statements in depth.

The Infinite Loop: A Programmer's Nightmare

An infinite loop occurs when a loop executes forever because its terminating condition never becomes false (for a while loop) or it never exhausts its iterable (for a for loop, though this is less common). This is typically due to an error in the loop condition, variable initialization, or the logic that's supposed to change the condition's state.

Common causes:

whileloop: Forgetting to update the condition variable inside the loop.

python

DANGER! This is an infinite loop if uncommented and run!

x = 1

while x > 0:

print("This will print forever!")

# Missing x = x - 1 or similar update

- Incorrect logic: A condition that's always true.

python

DANGER! Another infinite loop!

count = 0

while count != 5: # If 'count' never actually reaches 5 due to logic error (e.g., increments by 2)

print(count)

count += 2

Stopping an infinite loop usually requires force-stopping the program (e.g., pressing Ctrl+C in a terminal or using the stop button in your IDE). Always double-check your while loop conditions and ensure that there's a clear path for the condition to eventually become False.

for vs. while: Choosing the Right Tool

Deciding between a for loop and a while loop is a common programming decision. While sometimes either can achieve the desired outcome, one is often a more natural and readable fit.

| Feature | for Loop | while Loop |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Use | Iterating over a sequence (list, string, range) | Repeating as long as a condition is true |

| When to Use | - Number of repetitions is known in advance. | - Number of repetitions is unknown. |

| - Processing each item in a collection. | - Waiting for an external event. | |

| - Iterating a specific number of times. | - Looping until a user provides valid input. | |

| Control | Automatically handles iteration count/elements. | Requires manual initialization and update of condition variable. |

| Safety | Less prone to infinite loops (unless iterating over an infinite generator). | More prone to infinite loops if condition logic is flawed. |

| Readability | Often more concise for sequence iteration. | Can be very clear for conditional repetition. |

| The Rule of Thumb: |

- If you're dealing with a collection of items (like a list, tuple, or string) and want to do something to each of them, or if you need to repeat something a fixed number of times, lean towards a

forloop. - If you need to keep doing something as long as a certain condition remains true, and you don't necessarily know how many times that will be, a

whileloop is likely the better choice.

Beyond the Basics: Nested Loops and Modern Alternatives

As your programming skills grow, you'll encounter more complex scenarios involving loops.

Nested Loops: Loops Within Loops

Sometimes, you need to iterate over data that has multiple dimensions, or perform an action for every combination of items from two or more sequences. This is where nested loops come in – a loop inside another loop. The inner loop completes all its iterations for each single iteration of the outer loop.

python

Printing a multiplication table (e.g., 1x1 to 3x3)

print("Multiplication Table:")

for i in range(1, 4): # Outer loop for rows

for j in range(1, 4): # Inner loop for columns

print(f"{i} x {j} = {i*j}", end="\t") # \t for tab spacing

print() # Newline after each row of multiplication

In this example, for i = 1, the inner loop runs for j = 1, 2, 3. Then for i = 2, the inner loop runs again for j = 1, 2, 3, and so on. Nested loops are fundamental for tasks like matrix operations, generating combinations, or searching through multi-dimensional data structures. However, they can impact performance if too many levels are nested or if the collections are very large. To keep your code running smoothly, consider optimizing your code when using complex nested structures.

List Comprehensions and Generator Expressions (Pythonic Alternatives)

In modern Python, for many common iteration patterns, especially those involving lists or other sequences, there are more concise and often more performant alternatives to explicit for loops.

List Comprehensions provide a powerful, one-line way to create lists based on existing iterables.

python

Using a for loop to create a list of squares

squares_for_loop = []

for x in range(1, 6):

squares_for_loop.append(x * x)

print(f"Squares (for loop): {squares_for_loop}")

The same task with a list comprehension

squares_comprehension = [x * x for x in range(1, 6)]

print(f"Squares (list comprehension): {squares_comprehension}")

List comprehensions are readable, efficient, and a favorite among Python developers for transforming or filtering lists.

Generator Expressions are similar to list comprehensions but create an iterator (generator object) instead of immediately building the entire list in memory. This is especially useful for very large datasets where creating the whole list at once would consume too much memory.

While these alternatives don't replace loops entirely, they offer elegant solutions for specific iteration patterns, enhancing code readability and performance in many situations.

Navigating Common Pitfalls and Best Practices

Even with such fundamental constructs, there are common traps programmers fall into. Being aware of them, and following best practices, will save you considerable debugging time.

Watch Out For:

- Infinite Loops: As discussed, this is the most notorious loop error. Always ensure your

whileloop's condition will eventually become false. Forforloops, ensure the iterable isn't infinite (e.g., a custom generator that never stops). - Off-by-One Errors: A classic mistake where a loop runs one time too many or one time too few. This often happens with

range()(is the upper bound inclusive or exclusive?) or when comparing<vs.<=inwhileloops. Test your loops with edge cases (empty lists, single-item lists) to catch these. - Modifying a Collection While Iterating: If you add or remove elements from a list (or other collection) while you're iterating over it, you can encounter unexpected behavior. The indices might shift, causing items to be skipped or processed multiple times. If you need to modify a list, often it's safer to create a new list or iterate over a copy of the original.

- Inefficient Nested Loops: Deeply nested loops, especially over large collections, can lead to very slow code. Remember that a loop nested two levels deep runs the inner loop

N*Mtimes (where N and M are the sizes of the outer and inner iterables, respectively). Always consider if there's a more efficient algorithm or data structure. Learning effective debugging techniques will be invaluable here.

Best Practices:

- Clarity Over Cleverness: Write loops that are easy to understand. While list comprehensions are great, sometimes a multi-line

forloop is clearer for complex logic. - Meaningful Variable Names: Use descriptive names for your loop variables (e.g.,

for customer_name in customers:instead offor x in y:). - Minimize Work Inside Loops: Avoid performing computationally expensive operations repeatedly inside a loop if the result of that operation doesn't change with each iteration. Calculate it once before the loop.

- Use

forwhen you know counts,whilefor conditions: Stick to the strengths of each loop type for clearer, more maintainable code. - Comment Complex Logic: If a loop's condition or internal logic is particularly tricky, add comments to explain its purpose and how it works.

- Test Your Loops: Always test your loops with various inputs, including empty sets, single items, and large datasets, to ensure they behave as expected.

Your Next Step: Putting Loops to Work

Looping and iteration mechanisms are more than just programming constructs; they're a mindset. They represent the ability to identify patterns, automate repetition, and scale your solutions from simple scripts to robust applications. From processing vast datasets to building interactive user experiences, loops are the workhorses that make it all possible.

By now, you should have a solid grasp of for loops, while loops, and how to control them with break and continue. You understand the importance of iterables and the dangers of infinite loops. The journey of mastering programming involves not just knowing these tools, but also knowing when and how to apply them effectively.

The best way to truly internalize these concepts is to practice. Take a small, repetitive task you do manually and try to automate it with a script using loops. Experiment with different types of loops, try nesting them, and deliberately introduce break and continue to see their effects. As you continue to build out your programming toolkit, you'll find that these fundamental looping mechanisms are often combined with other core programming concepts, allowing you to build reusable code with functions and much more.

Ready to see how these core concepts integrate into larger systems? Learn how it works when advanced automation relies on precise iterative control. Your code's efficiency, readability, and reliability will thank you for it.